Subverting the floral metaphors for menstruation

Published on Scroll.in

23 November 2025

Touch a flower on your period and it will wither away, women are told. Yet, as symbols of fertility, flowers have become a euphemism for the menstrual cycle.

While growing up in Kenya, I was cautioned by my mother not to touch the curry plant when on my period. She left me with the impression that something in my body would contaminate the plant, prompting a feeling of deep self-revulsion.

One afternoon, when I was on my period and alone, I went into the garden and touched the curry plant. Nothing happened – not even when I pressed the leaf between my palms and stroked the branches. I monitored the plant, and after a week, I told my mother that she had been mistaken: there was nothing noxious in my body.

She replied, I was lucky the plant hadn’t died, and to never do it again because it would the next time. Later, I learnt that this was a common Kenyan-Asian belief.

Across South Asia, menstruating women face restrictions on their movement, choices and opportunities. These norms include not touching growing crops, fruit trees and certain plants and flowers. This taboo is connected to the myth of a woman’s bodily impurity during menstruation: that if she touches certain flowers, especially those like marigolds, lotuses, or hibiscus, which are used in religious rituals, the flowers will wither or die, and contaminate the offering to the deity.

But flowers are closely tied to menstruation.

As flowers are symbols of fertility, floral and horticultural euphemisms for menstruation are common in South Asia. Menstrual product companies and period tracking apps have utilised floral associations for their logos and on packaging materials. At the same time, writers and artists have powerfully subverted these floral associations to challenge menstrual taboos and stigma.

Widespread myths

In Nepal, particularly in the rural areas, it is believed that trees will fail to bear fruits if touched by a menstruating woman. In Bhutanese Buddhist culture, menstruation is symbolised and mirrored in the life of a flower. In Tantric Buddhism, the word for a woman’s vagina is “pema” or lotus, and nectar from the lotus refers to menstrual blood. Embedded in the symbol is the idea that the lotus grows in muddy water but in spite of this, blooms white and pure. Likewise, menstruation is dirty but nonetheless sacred.

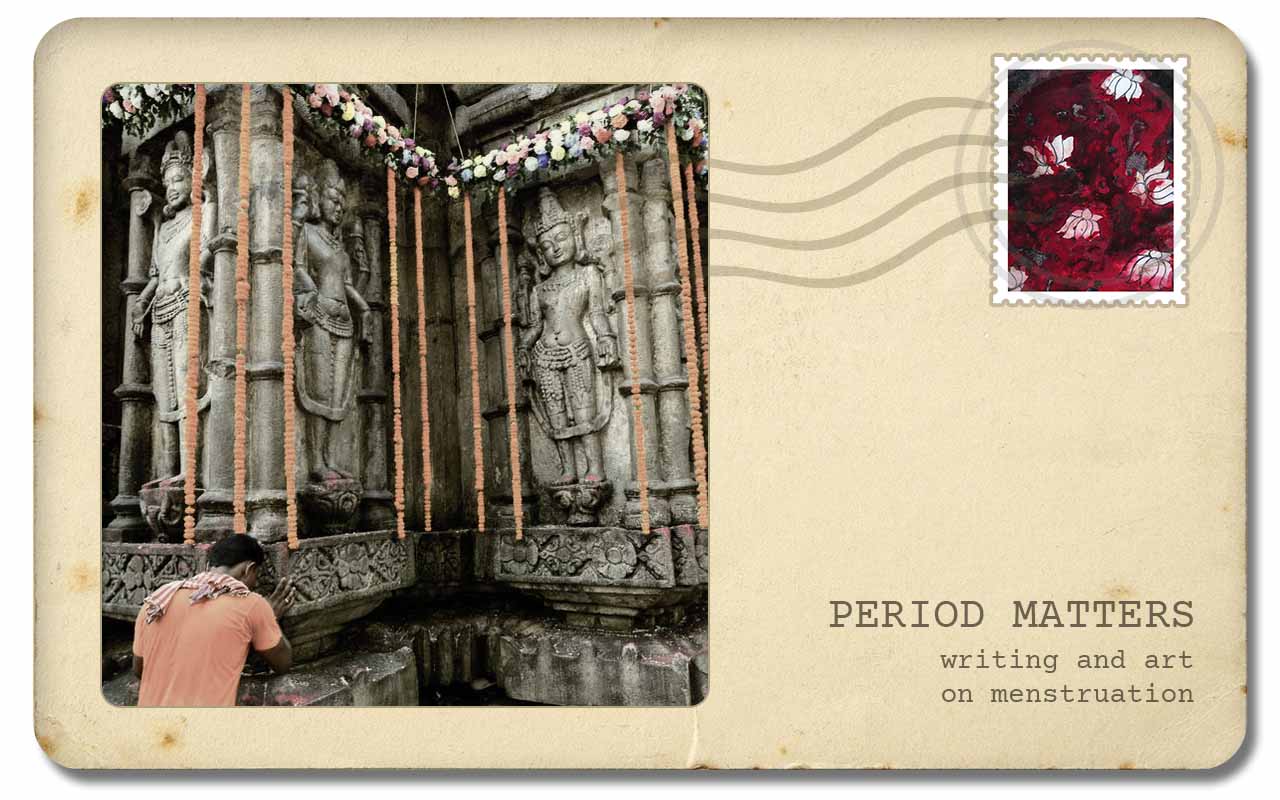

In Hindu rituals, flowers are symbols connected with menstruating goddesses. During the Ambubasi festival in India, when the goddess Maa Kamakhya is believed to be menstruating, devotees are forbidden from picking flowers or touching plants. The temple is decorated with red hibiscus before the festival begins and at the end, the aparajita flower is offered.

Flowers are used in representations and rites of Hindu goddesses like Lakshmi, who is depicted holding a lotus and sitting on a lotus throne, and Kali is often decorated with red hibiscus.

Similarly, among the Santhal Adivasis in Jharkhand, menstruation is referred to as “hormo baha” or flower of the body; “hormo” means body, and “baha” is flower.

Floral metaphors

Flowers as metaphors for menstruation are linguistically fluid. For my edited book, Period Matters: Menstruation in South Asia, I reimagined English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem What if?, which represents a long tradition of flowers in dreams with allusions to transcendence.

In my poem, the line: “What if you slept and dreamed… and you awoke with a flower in your hand?” is subverted with the flower replaced by a broom, turning the romantic vision into a nightmare. The poem is based on interviews I conducted, during 2020, with women from the Lahore sweeper community, who shared how they swept and cleaned roads, but had no access to public washrooms or menstrual products because Lahore had so few public washrooms for women, and even as of 2024, only about 10 exist.

The poem destabilises the flower as a metaphor to show how for many women involved in menial labour there is no space for dreaming. It illustrates how the flower metaphor is not always liberating, and how a literary floral tradition can be disrupted.

Artist Lyla FreeChild’s painting is another example of destabilising the flower image with a deeply political message. It was inspired by a dream where she saw herself as the Hindu goddess Lajja Gauri, associated with fertility.

When depicted as a sculpture, the goddess is usually naked, with a blossomed lotus head while seated in a birthing position. The goddess holds a lotus in each hand, and blooming lotuses are etched on her body to depict the seven chakras. During rituals to Lajja Gauri, devotees use lotuses to emphasise purity and rebirth.

In FreeChild’s self-portrait, Aadya Shakti, the artist is portrayed as the goddess menstruating, a crimson sea with lotuses flowing from between her legs. The painting centres the lotus as a symbol of the divine feminine thriving in menstrual blood. For her artwork, FreeChild used menstrual blood.

The artist also sought to reclaim the lotus from the Hindutva politics of the Bharatiya Janata Party, which uses the lotus as its symbol, highlighting how flower motifs can be weaponised for political ends.

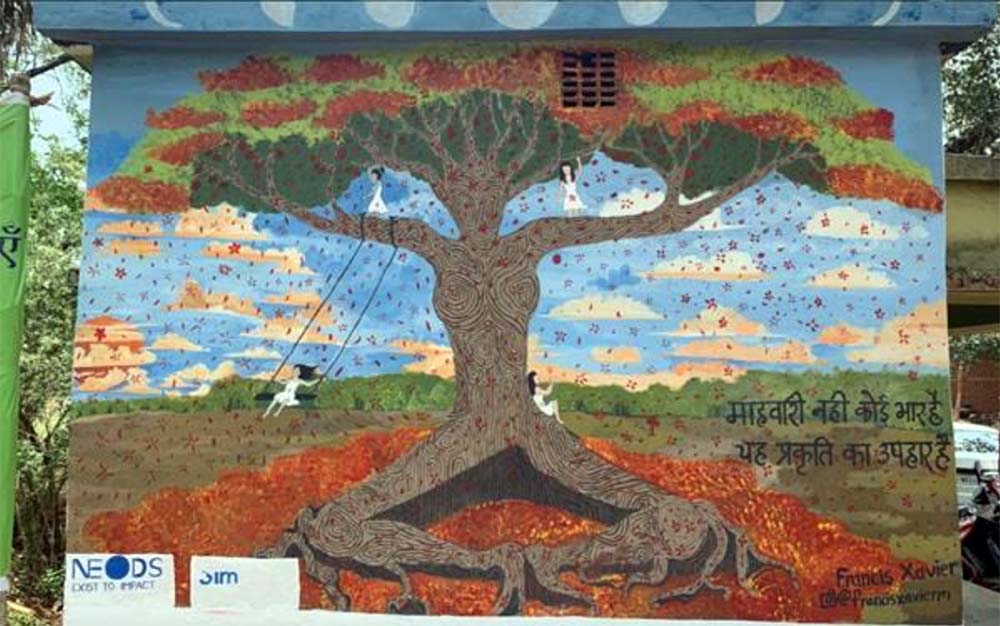

Red flowers like the hibiscus and gulmohar are also associated with menstruation. In 2019, a group of youngsters guided by educator/activist Srilekha Chakraborty in Naya Bhadiyara village in Jharkhand raised awareness about menstruation and painted a wall mural outside the post office in the village. The mural showed a gulmohar tree in the shape of a woman’s body, with branches as arms reaching upwards and a crown of deep-red flowers with petals falling. By connecting menstrual with nature, the mural illustrated that menstruation was natural, a time of beauty and creative potential.

Similarly, in Raqs-e-Mahvaari, a dance commissioned for the Period Matters book, the dancer Amna Mawaz Khan wears a red flower in her hair. She performs the dance in an office space, rather than a studio, to emphasise that menstruating women should not be shamed in workspaces. Here, the gulmohar becomes a symbol of defying gendered discrimination.

With strong arm movements, pivot turns and expressive mudras forming the outline of flowers, Khan portrays menstruation as a blooming, cyclical and biological movement through the body. Her floral gesticulations illustrate menstruation as an unfolding, budding flower.

Similarly, Indian artist Rah Naqvi’s uses flowers as a symbol of protest and to render visible what is kept hidden. Their art involves using red thread, sequins, beads and buttons to make embroidered flower patterns on a pair of underpants, pad and tampon, thus rendering what is considered “dirty” as ornamental. Naqvi’s menstrual art with floral motifs also defies concealment by normalising what is considered taboo to emphasise it as natural and therefore acceptable to speak openly about.

Beyond the realm of art

Floral associations with menstruation have also found use as branding: like period-tracking apps and menstrual products. Many period tracking apps use flower aesthetics as part of their logos, widgets or visual themes. The Period Tracker app, P-Tracker, has a daisy-like pink flower with a yellow centre as its logo, and a flower symbol for fertility tracking.

Anandi, India’s first bio-compostable pad, has a logo with a variety of herbs and flowers, to imply environmental sustainability. Global brand Libresse uses a blue and pink vulva-inspired floral motif, while Days For Girls, an NGO working on menstrual health, has a stylised yellow flower as a logo.

Flower logos and visuals are also popular for menopause products, but some consumers have resisted this trend. An essay in The Atlantic pointed out: “Hearts. Pink. Flowers. Pink flowers! Is this really what women want? For products ostensibly aimed at adult women, period-tracking apps look awfully like the girls’ aisle of a toy store.”

Revisiting flower motifs on menstrual products prompted me to recall when my sisters and I were supplying underwear and pads to women in a Kenyan prison. Each inmate was to get four pairs with random colours and designs. During the distribution, a fight broke out because many of the women wanted underwear with floral patterns. It was an unexpected reminder of how women, wherever they are, associate flowers with the feminine.

It brings to mind how writer Ismat Chughtai powerfully linked flowers and blood to resilience: “Flowers can be made to bloom among rocks. The only condition is that one has to water the plant with one’s heart’s blood.” Chughtai’s imagery is a reminder that what a society or culture deems impure or hidden is, in fact, a source of resilience and renewal.

.