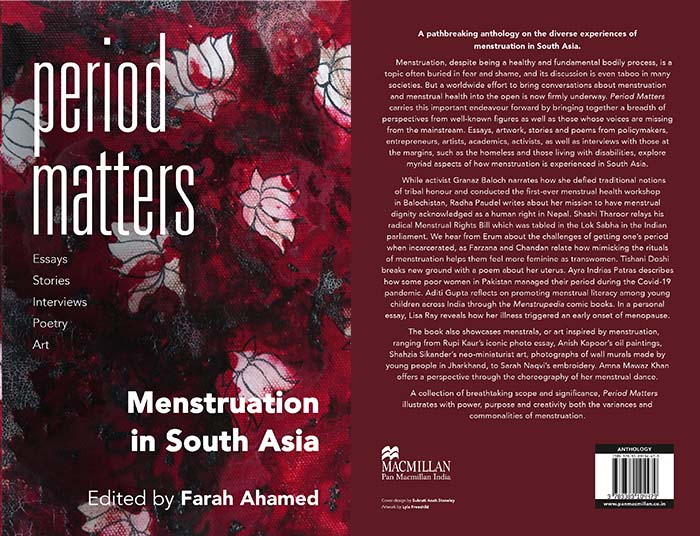

About Period Matters

This volume carries a breadth of perspectives: those of politicians and policymakers, entrepreneurs, artists, academics, students, nuns, activists, poets, prisoners and the homeless. It provides a glimpse into the way menstruation is viewed by people from different backgrounds, religions and classes.

Alongside the well-known artistic and academic contributors are those who are usually missing from the mainstream discussion on the subject. Each essay, artwork, story or poem explores a different aspect of how menstruation is experienced in South Asia.

Tashi Zangmo’s essay explores the context of the Buddhist nuns of Bhutan and recounts her ongoing efforts with the Buddhist Nuns Foundation to revolutionize menstrual health in the nunneries. Activist Granaz Baloch explains in her essay how she defied traditional notions of tribal honour, or Baloch Mayar, and conducted the first-ever menstrual health workshop in Balochistan. Radha Paudel, who has been working in Nepal over the past thirty years, writes about her mission to have menstrual dignity acknowledged as a human right. Shashi Tharoor relays his radical Menstrual Rights Bill which was tabled in the Lok Sabha in the Indian parliament. Meera Tiwari’s research on Uttar Pradesh and Bihar utilizes a ‘menstrual dignity framework’ to analyze data collected from street theatre performances. Radhika Radhakrishnan puts forward the case for period leave in the workplace, and women from Bangladesh share the difficulties of bleeding in the workplace and at school. Novelist Shashi Deshpande, whose fiction openly mentions menstruation, narrates her own story of menstruation and how she grew out of the shame and misconceptions associated with it.

We hear about the challenges of getting one’s period when incarcerated in Pakistan from Erum. Farzana and Chandan relate how mimicking the rituals of menstruation helps them to feel more feminine as transwomen, and Javed, a transman, shares his trauma of dysphoria.

In her poems, Victoria Patrick imagines the hardships of the women menstruating during the traumatic days of Partition and the homeless women who have to cope with menstruation without even the most basic of amenities. Srilekha Chakraborty offers her insights into working with India’s indigenous Adivasi community. Tishani Doshi shares two poems, one about her relationship with her uterus and the other as a note for mansplainers. Zinthiya Ganeshpanchan looks at how women from the Sri Lankan diaspora practise menstruation rites and rituals. Prachi Jain and Anshu Gupta talk about NGO Goonj’s efforts to help women cope with their periods during natural disasters like cyclones and floods and in the aftermath of communal riots.

Ayra Indrias Patras describes how a mother helps her daughter with a mental disability to manage her period and how poor women in Pakistan managed their periods during the Covid-19 pandemic. She also underlines the case of the female Christian sweeper community of Lahore, who have no access to public washrooms. In a personal essay, Lisa Ray writes about how her illness and the consequent treatment affected her menstrual cycle and triggered an early onset of menopause. Mariam Siar highlights how different her understanding is from other women in Afghanistan, and through a Proustian lens, Siba Bartataki reflects on memory as loss, and how writing about menstruation can be about reclaiming a forgotten part of one’s identity.

Farah Ahamed‘s essay on the male and female writer’s gaze when writing about menstruation in fiction, reveals how authors have either compassion for their menstruating characters or objectify them. In the two short stories, authored by Farah and K. Madavane , they illustrate the obsession and fascination with menstruation which exists simultaneously with feelings of revulsion and unfamiliarity. Farah was moved to write her story after interviewing homeless women living near a shrine in Multan, and when she watched Meesha Shafi’s music video Hot Mango Chutney Sauce, after which the story is titled, it felt integral to the story. The poem, What If, is based on her observations of the sweeper women in Lahore.

Discussing innovation and entrepreneurship, Aditi Gupta reflects on promoting menstrual literacy among young children across India through Menstrupedia’s comic books. Alnoor Bhimani expounds on how period-tracking apps construct the self, and Jaydeep Mandal recounts his journey to creating India’s first compostable and biodegradable pad at Aakar Innovations.

Apart from writing, Menstrala (art inspired by menstruation) plays a powerful part in this anthology: Rupi Kaur’s photo essay, reproductions of Anish Kapoor’s oil paintings, Lyla Freechild’s menstrual blood art and Shahzia Sikander’s Neo-Miniaturist art, photographs of the wall murals made by young people in Jharkhand and Sarah Naqvi’s delicate needlework. And with graceful movements, Amna Mawaz Khan offers a perspective on menstruation through the choreography of her menstrual dance. Each artist, using his or her preferred medium, has shone light on different aspects of menstruation.

To condense the plurality and complexity of menstruation in a single book is a daunting task, but the originality of Period Matters lies in how disparate genres and forms of art and writing in this collection illustrate both the variances and commonality of the experience.