MY UGANDAN FRIENDS have an expression, “Joke equals truth,” and it started as a joke. When my edited anthology Period Matters: Menstruation in South Asia was published last year, my sister said to me, “Now every man who’ll ever read your book will know about your first period. Doesn’t that feel weird?” I laughed, but then I realized that, by being open about a subject I felt needed to be discussed more authentically, I’d lost my “privacy” about an intimate bodily experience. I told myself it didn’t really matter since, after all, periods are a normal biological phenomenon. But back then, I had no way of anticipating how men would react to me or my book. And I had yet to realize that, while raising awareness about period poverty may be acceptable, discussing the shame around the female body is still taboo.

My interest in the problems faced by girls during menstruation goes back 20 years, to when I was working in Uganda and first read about how underprivileged girls and women managed their menstrual health. I had not before then heard about girls missing school because of a lack of access to menstrual products, poor sanitation, and inadequate toilet facilities. I was shocked to realize that, while the privileged enjoyed the luxury of choice in menstrual products, the poor had none. After that, it took 10 years for the idea of taking action to ferment and develop into a concrete plan.

In 2011, my two sisters and I established an informal initiative in Kenya called Panties with Purpose. Our objective was to promote menstrual health and raise awareness about the detrimental effects of girls missing as many as 60 days of school a year because of a lack of access to menstrual products. Since then, Panties with Purpose has reached over 16,000 girls and distributed more than 60,000 pairs of underpants and nearly as many pads.

Some years after, when I’d moved to the United Kingdom, I was contacted by a priest whom I shall call Father John. He wrote saying that he’d heard about Panties with Purpose and wanted to get involved. I met Father John in a café. A middle-aged white man, he was wearing his black coat and priest’s collar. He told me how he’d been in Nairobi for a conference and had there met a woman who had taken him to visit a school. At the school, he learned about the problems of period poverty. As he was speaking, I couldn’t help but notice how his voice became excited and his face red and sweaty. I saw the flakes of dandruff on the shoulders of his coat, and his long, yellow fingernails. He insisted that he knew all about the difficulties of periods and said, “I can do something to save those innocent girls.” I beat a hasty retreat. At the time, I saw it as a one-off meeting with a sick man, never realizing that, in the future, I’d be confronted by a whole tribe of them.

Between 2017 and 2019, while traveling through India and Pakistan, I spoke to girls and women about menstruation and learned about their local values and practices. While some stories were universal and similar to those I had encountered in East Africa, others were specific to their context. It occurred to me that the diversity of menstruation could best be reflected in a book that included both fiction and nonfiction. My decision to focus on South Asia was motivated by two events. The first was when, as I was about to enter a Jain temple in India, I was stopped by a male security guard who then asked if I was menstruating. The second was when I picked up a packet of sanitary pads while shopping at a supermarket in Pakistan and a male shop attendant rushed over and told me to hide them in a brown bag to avoid being humiliated at the checkout counter. I found both incidents disturbing—being questioned by a stranger about intimate details of my body and having my behavior in a public space controlled because menstruation was associated with shame.

Period Matters features over 40 different perspectives: those of politicians and policymakers, entrepreneurs, artists, academics, students, nuns, activists, poets, prisoners, and the homeless. Through an intersectional lens, it provides a glimpse into the way menstruation is viewed by people from different backgrounds, religions, and classes. Alongside the well-known artistic and academic contributors are those who are usually missing from mainstream discussions on the subject. Each interview, essay, artwork, story, dance, or poem explores a different aspect of how menstruation is experienced in South Asia.

Period Matters also includes a range of male contributors and shows how they engaged with the subject. Take, for instance, the visuals of artist Anish Kapoor’s larger-than-life red and black paintings Blood Hole and Out of Me; politician Shashi Tharoor’s Menstrual Rights Bill, which emphasizes menstrual dignity as a human right; entrepreneur Jaydeep Mandal’s journey to designing a compostable pad; academic Alnoor Bhimani’s analysis of the subversive qualities of digital period-tracking apps; or novelist K. Madavane’s short story about a young boy’s understanding of his sister’s first period.

These are some of the positive ways in which men have approached the subject in Period Matters; however, in my essay “Menstruation in Fiction,” I discuss somewhat obsessive and horrific depictions from some of the world’s leading male authors. For instance, in his 1984 novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera, as author-narrator, makes a bizarre comparison between Tereza’s period and that of her dog, Karenin: “Why is it that a dog’s menstruation made her lighthearted and gay, while her own menstruation made her squeamish? The answer seems simple to me: dogs were never expelled from Paradise.” The degradation is palpable; for Tereza, women are sinful and repellent, of a lower status than dogs. Another example is Ammar Abdulhamid’s 2001 novel Menstruation, which is set in Syria, and in which the character Hassan believes that menstrual blood is “the true source of all evil in the world” while pregnancy is “an infant vampire nursed on menstrual blood.” His supernatural senses enable him to detect the instant when “a medium-sized spurt of deep, dark, almost tarred blood” has filled a tampon. These are just two examples, but there are many other instances where male authors from varying cultural backgrounds have shown little compassion towards their female characters. By surrounding the subject of menstruation with obsessive sexual fantasies, myths, and superstition, male authors have depersonalized and objectified their female protagonists, divesting them of basic humanity and robbing them of dignity and power. When I wrote that essay, I had no inkling that one day I would be victimized in a similar way.

Period Matters was published in summer 2022. Since then, not a week has passed without some random male sending me an article or a link on the subject of menstruation. These men are not friends but those who have contacted me through social media platforms. At first, I thought they were “supporting” the book. But as time passed, and the messaging continued without any prompting from me, I began to wonder what it was that motivated them to contact me. When I blocked a male on one platform, he followed me on another, and sent me more YouTube and TED Talk links. Maybe he thought he needed to help me understand the subject better? I didn’t take any of this seriously, until it became more uncomfortable.

One of the first panels I did for Period Matters was at a UK university and was moderated by a male academic. During the session, he explained to me what the most “important issues” were for menstruators, interpreted the questions from other panelists, and even found it necessary to state that he was a modern, open-minded man and appreciated the importance of having conversations around menstruation. I realized that even if a woman is speaking about her own experience, a man feels that he must have the last word. Of course, not all men. But enough have shown me over the past 12 months that when it comes to the subject of periods, they think they know best.

The most recent example was when I was in Kenya and telling a man about Period Matters. The man, a middle-aged Asian in his early sixties, listened for about 30 seconds before interrupting me to say that he had “firsthand knowledge about those things” because he knew how “when girls don’t have pads they use feathers or they miss school.” I recoiled at how flippantly he spoke about such serious issues of period poverty, while he carried on explaining how he’d supported a school in rural Kenya with menstrual products. Of course, I appreciated what he’d done to help, but his savior attitude, and his tone as he spoke about how “good” he’d felt “assisting” girls to manage their bodies, made me flinch.

He reminded me of a character from a short story, “Poached Eggs,” that I’d written some years ago about a newly wedded couple. One day, the husband, Jaffer, gives his wife, Nuru, a calendar and a red pen and asks her to “mark those days you’ll be sleeping in the other room with an X.” Confused, Nuru asks him what he meant. Jaffer explains that when Nuru is on her period, she must spend the night in the guest room, and the calendar will enable him to know the dates in advance. It is not evident whether Jaffer thought Nuru was “unclean” during her period, had a phobia about menstrual blood, or was just plain terrified because he didn’t understand what a period entailed. But what I wanted to show was that by monitoring Nuru’s menstrual cycle, Jaffer gained a sense of authority and security. In fiction, his controlling behavior may at one level appear humorous, but in reality, it has more sinister implications.

In her 2012 essay “Men Explain Things to Me,” Rebecca Solnit explores how women’s views are considered unreliable in men’s minds and argues that, because of this attitude, violence, abuse, harassment, and rape are often discounted. She highlights how, no matter what a woman says, a man seemingly believes that he always knows better:

Men explain things to me, and other women, whether or not they know what they’re talking about. Some men.

Every woman knows what I’m talking about. […]

And no man has ever apologized for explaining, wrongly, things that I know and they don’t.

Obviously, no two men have the same understanding of menstruation, and some have no knowledge at all. It is no wonder, then, that when they first hear about periods and the myths surrounding them, men became alarmed. While for some men it is a frightening topic, for others it is some kind of perverse fantasy. Because “X” is not something they can imagine or relate to, it isn’t normal, and therefore a woman becomes alien, or even subhuman.

Menstruation denial is a common way that men deal with periods. When I told an Asian man in his late seventies about Period Matters, he became confused. “Is it for public consumption?” he asked, as if I’d told him I’d been writing about something forbidden or pornographic. I thought it would be interesting to get a male perspective on the book, so I approached a well-known Indian cultural commentator to review only the male contributions in Period Matters. He replied that he was “not qualified to comment.” Similarly, a reputable Black Kenyan academic refused, saying that “the subject is tricky.” A UK-based, white, middle-aged literary agent argued that he could not take on the book; he argued that there was no market for it since “everyone knows what a period is, and the subject has been discussed exhaustively.” Until this point, I had found it all quite amusing, until things suddenly became darker.

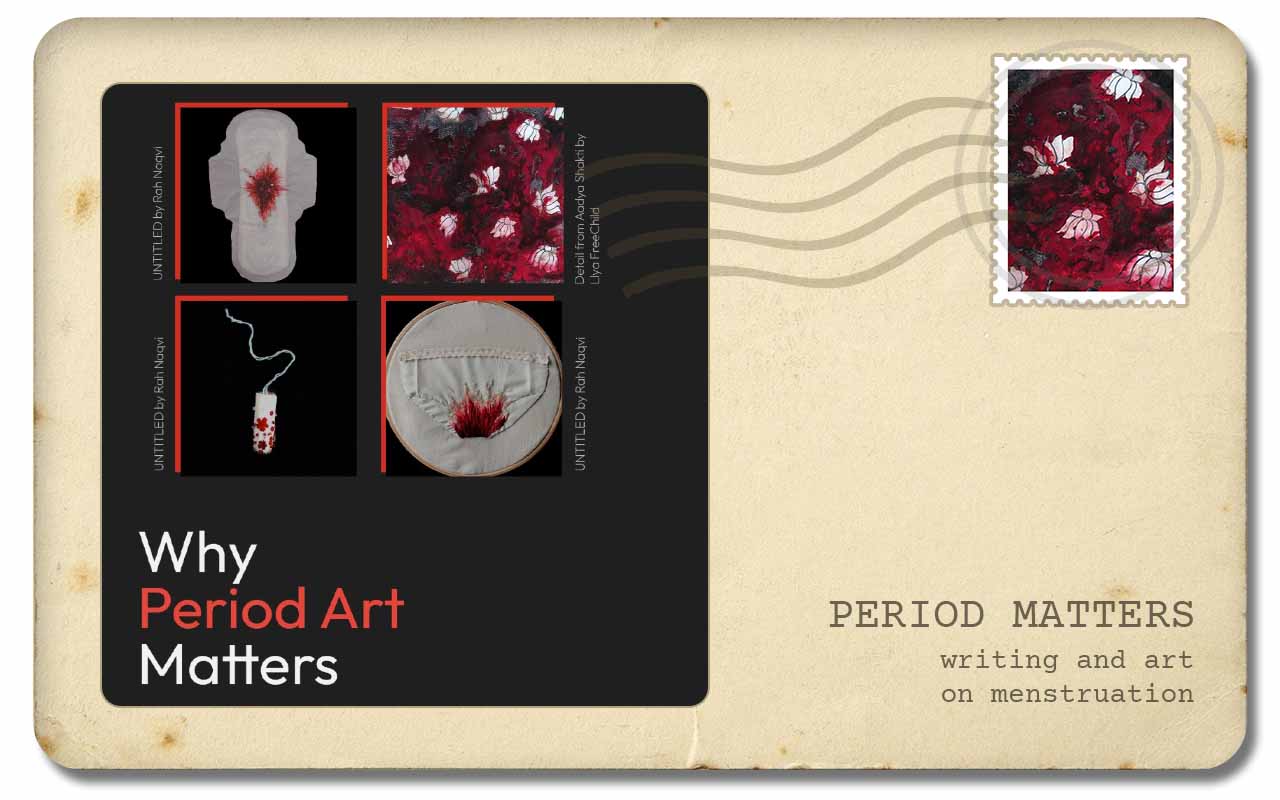

It all started when I conducted a workshop at a university in Lahore, Pakistan, entitled “Why Period Art Matters,” which examined a variety of artistic interpretations of menstruation in film, dance, advertising, poetry, and sculpture. My aim had been to highlight the diversity of menstruation and the fact that there was no “normal” or singular way of understanding it. The poster marketing the event had the visuals from Period Matters of Rah Naqvi’s embroidery and beadwork on a tampon, a pad, and a pair of underpants, their intention being to make visible and beautiful objects usually kept “out of sight” and considered “dirty.” When the Lahore community saw the poster, however, they called for the event to be canceled, saying it was a step too far—how could something so shameful be called art or considered artistic? It was indecent, they claimed, and I was encouraging immorality. The university, nevertheless, decided to go ahead with the event, but with restrictions. They removed the poster from social media and reinforced security on campus. On the day of the workshop, 40 participants showed up to discuss aspects of period art. Little did I know that, a day later, I would be charged with promoting liberal ideas and criminal behavior, and with polluting young people’s minds. The intensity of the anger directed at me, and the desire to protect the shame and idea of dirt around menstruation, shocked me.

I was mistaken in thinking the university incident would be forgotten. Two months later, an Islamic fundamentalist network posted a video on YouTube about the workshop and Period Matters. The so-called “senior analyst,” a bearded man in Pakistan, accused me of promoting anti-Islamic ideas in the same way Salman Rushdie had in his 1988 novel The Satanic Verses. I was, in short, doing the work of the devil. He spoke using inflammatory words to incite hate against me, and all women like me, who dare to speak about women’s bodies in public. He repeated my name in a tone filled with loathing and disgust, asking for morally upright people to be put on “notice” about me: a corrupt, evil woman tampering with their religion, one of their most ancient tools for protecting women’s modesty. Earlier this year, I’d participated in an online event at a Berlin bookshop in solidarity with Rushdie after he’d been attacked. I read an excerpt from his 1990 essay “Is Nothing Sacred?” in which he’d argued why fiction was important. My participation in the Berlin event had nothing to do with anything religious, just as Period Matters has nothing to say about any religion, so for the “senior analyst” in the video to connect Period Matters with The Satanic Verses was illogical. Yet the implications of his threats not only for my own security, but also for that of any woman who tries to assert her rights, are unimaginable. The joke had turned into a nightmare.

Some men have tried to trivialize the episode. One wrote to me saying, “Congratulations, you’re famous,” while another said, “Propaganda against you is motivated by jealousy,” and still another wrote, “Forget about it, people will find someone else to bark at tomorrow.” I realized that I was living out Solnit’s words: women’s voices have no integrity in men’s minds, so violence against women is not taken seriously.

Period Matters includes my short story “Hot Mango Chutney Sauce,” in which I fictionalize the culture of surveillance around women’s lives and bodies. In my story, a group of men who work in the kiosks in a parking lot outside a shrine in Pakistan observe five homeless girls. The girls have no privacy. The men monitor how the girls’ bodies change as they become adolescents. The men find rags and dried blocks of ash in the public washrooms and make vampire jokes about the “dirty blood.” They jest loudly when a girl is absent from the shrine steps and say it must be because she is on her “X” days. As the narrative unfolds, the girls begin taking their own lives one by one to protect themselves from the prying eyes of men. Truth, not joke.

A year on since the publication of Period Matters, I have a better understanding of how those in authority want to preserve myths of purity and a renewed appreciation of the meaning of terms like “dirty,” “shameful,” and “taboo.” I’ve been the target of deep-rooted patriarchal misogyny, but I have also experienced how art, in its varied forms, has the power to upset the status quo and transform conversations.

Published on Los Angeles Review of Books.